Last Saturday I braved the heat and the crowds and made my way down to Kamakura, the once former capitol of Japan, and thus home to many wonderful temples and shrines, and to the Daibutsu (Big Buddha) statue. Kamakura is also home to many varieties of seasonal flowers, and it was one of them, the ajisai or hydrangea, that brought out the crowds in droves on this day. At the Meigetsuin temple, so reknown for it’s ample collection of hydrangea that its nickname is ajisai-ji or “Hydrangea Temple,” I could hear tourguides bellowing out through their bullhorns to their charges waiting in line that they would have to wait at least 1 hour before they could get into the temple. There were the requisite moans, but I didn’t see any of them get out of line.

Fortunately, I was in Kamakura for quite a different attraction, one much more subdued and less-traveled by comparison: an exhibition of miscellany related to the life and career of Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, on view at the Kamakura Museum of Literature. The day before, I had been flipping channels on the TV when Naoko caught Ozu’s name on the screen and told me to stop. It was a news segment on the exhibition, which I had not been aware was going on. I was lucky, the exhibition was to end on the 29th of this month. There was still time to go see it, and so I did.

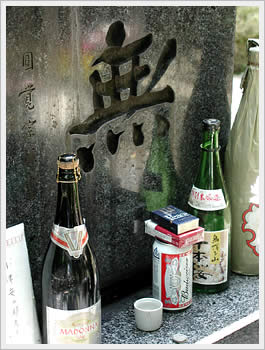

The museum is in Kamakura proper, not too far from the Daibutsu, but I began the day’s journey with a stop in Kita-Kamakura, and a visit to Engaku Temple, on the grounds of which is a cemetary with Ozu’s grave. Inspired by Jonathon Delacour‘s post “Visiting Ozu’s grave”, I had traveled down to Kamakura in July of last year in search of the gravesite, and after some missteps and wrong turns, and not a few rows of grave markers scrutinized heavily, I was finally able to find the austere granite block upon which is inscribed the Chinese character mu, which vaguely means “nothingness” or “non-existence.”

This time of course I was able to go straight there to pay my respects. In contrast to how the grave looked last year, on this occassion someone before me had left a kumotsu or “offering” of sake and beer and a couple packs of cigarettes. One of the cigarette packs was the Peace brand, and later at the exhibit the same distinctively packaged brand could be seen in a display of Ozu’s personal effects.

I continued on my way, with a vague plan to see the Hydrangea Temple, that is until I caught wind of the aforementioned tour guide’s announcement. So I passed the throng and continued my walk to Kamakura, meandering past some temples along the way, and continued to walk for a couple of kilometers to the Daibutsu (I had forgotten that when I first visited Kamakura in 1997, we had taken the Enoden train to the Daibutsu). After an almost obligatory visit to the Daibutsu, and some well-needed rest in the shade, I made my way over to the Kamakura Bungakukan, or Museum of Literature.

The museum is housed in a villa of the former Marquis Maeda, decendent of one of the most powerful feudal clans of the Edo era, and was originally built in 1890. The present Western-style structure dates from 1936, and was depicted by Yukio Mishima in his novel Spring Snow. While the property is large and spacious, the museum itself is quite tiny.

The Ozu exhibit, which was entitled mirai e gatari kakeru monotachi (loosely translated as “Things that speak to the future”), was of modest size, but did not disappoint. In two rooms, various examples of Ozu paintings and drawings were on display, as well as rare (to me, at any rate) photos of Ozu at various stages of his life. My favorite was a photo of Ozu as a 9-year old boy in a ceremonial sumo kesho-mawashi he had made out of paper.

There were display cases with various paraphernalia related to Ozu’s directorial work, notebooks, diaries, screenplay pages with drawings on them, his Leica rangefinder camera, the viewfinder he used when directing, the tripod his crew used to get the famed “tatami-mat” low-angle shots, and Ozu’s trademark white pikebou, or pique hat. I lingered for as long as I thought reasonable, trying to stave off the ephemerality of the visit.

I bought the small book that accompanied the visit, as well as a postcard set of reproductions of some Ozu drawings and watercolors, and have scanned those along with some other bits from the exhibit, and put them online. I’ve also finally created a site with directions on how to find Ozu’s grave at Engaku in Kita-Kamakura, which I had intended to put up online last year but never did. Both these sites can be accessed from here:

Note: I created these pages in some ways as a test for making a web page using both English and Japanese, and used Mozilla’s Composer for this. Composer is not my WYSIWYG html editor of choice, but it was a dream when it came to inputting both Japanese and English and having them render properly, even in code view. The pages look fine on my system (Windows, using Mozilla 1.3), but as I’m new to this, I would appreciate any feedback from users who might have trouble viewing the pages properly.

ADDENDUM: I should have noted that this Ozu exhibit will end on June 29th, so if you’re in the Tokyo area and interested, you’ll need to hurry. Also, when at the museum, I saw small handbills advertising some sort of Ozu event on the 29th, but I’m not sure exactly what kind of event, nor could I find any information online about it.